Translator’s Note: The following text is an approximate translation of a 16 June 2020 article written by Proekt.media founder and head editor Roman Badanin. The article is a unique document in that it approaches the COVID-19 epidemic through the lens of a singularly personal tragedy; Badanin’s mother-in-law, Lyudmila, passed away from coronavirus-related complications on 3 June 2020. To maintain the journalistic integrity of Badanin’s account, Proekt.media assigned a separate journalist Daniil Sotnikov, to substantiate certain of Badanin’s claims. – Allen Maggard, 20 June 2020

Translator’s Note: The following text is an approximate translation of a 16 June 2020 article written by Proekt.media founder and head editor Roman Badanin. The article is a unique document in that it approaches the COVID-19 epidemic through the lens of a singularly personal tragedy; Badanin’s mother-in-law, Lyudmila, passed away from coronavirus-related complications on 3 June 2020. To maintain the journalistic integrity of Badanin’s account, Proekt.media assigned a separate journalist Daniil Sotnikov, to substantiate certain of Badanin’s claims. – Allen Maggard, 20 June 2020

On June 3rd of this year, at 15:00 hours in the hospital named for Sergei Sergeevich Yudin, someone close to me died – my sons’ grandmother, my former wife’s mother. Proekt.media doesn’t have any other articles written in the first person, but this one will be. However, in order to avoid personal prejudices and professional ethical violations, another Proekt.media author accompanied me throughout the entirety of this text: as a journalist, he spoke with the individuals and institutions that I interacted with as a relative of the deceased.

This story illustrates the many issues facing Russian medicine during the period of the coronavirus pandemic.

Interaction

Lyudmila’s death at 75 years of age resulted from a pair of strokes which occurred during the last year-and-a-half of her life. The most recent one resulted in an emergency hospitalization at the Yudin city clinical hospital – popularly referred to as “Number Seven” – on May 18th. Number Seven is regarded as the best-equipped public rehabilitation clinic in Moscow. Prior to 2019, intensivist Denis Protsenko worked as its main doctor; today he heads the main coronavirus clinic in the country.

Near Number Seven’s main building on Kolomenskiy Lane, there stands a billboard with the words, “Thank you, doctor.” The main entrance to the clinic is nearby. It’s been closed to visitors since mid-March.

For the more than two weeks that Lyudmila was in the hospital, her relatives were unable to speak with the attending physician. They collect messages for the sick at the entrance, but when it comes to speaking with doctors, every department recommends calling by telephone during a specific window of time. For the neurology department, where Lyudmila ended up, the phone number is +74997823501 and is open for calls until 16:00 hours.

Lyudmila’s relatives called this number every day – as did the journalist from Proekt.media – waiting for an answer that never came. Older people might compare this situation with the process of phoning the information desk of Moscow train stations at the peak of the tourist season in Soviet times: the “busy” signal interspersed with long beeps, and so on, ad infinitum.

The best way to find out about a relative in a Russian hospital is to become acquainted with younger medical personnel. A nurse with the neurology department – I won’t reference her by name – was the only person who told the family about Lyudmila’s condition during the 16 days she was in hospital.

At four in the morning on June 3rd, this nurse notified the family about Lyudmila’s death (the attending resuscitation doctor later told relatives that he called the home phone at the deceased’s registered address – no one was there). When the relatives phoned, the doctor on call with the resuscitation unit stated that Lyudmila had “passed away from a cerebral infarction” and delivered his condolences.

| Kin without communications

“The situation is unusual, hospitals that previously didn’t work under such conditions have been refitted because of coronavirus,” explained medic and former Moscow deputy mayor for social issues Leonid Pechatnikov. “There are multichannel telephones in several recently-commissioned hospitals, in older ones, such lines are only just now being installed.” For example, in Moscow’s 52nd hospital, which was refitted for coronavirus, the doctors themselves solved this issue by setting up a call center. Surgeon Alexander Vanukov told Proekt.media: “From the outset, we decided that we cannot work like this, it’s inhumane enough as it is. We did a very simple thing: instead of two people, they put four, then six people on single multichannel telephone number, taught them what to say, how to extract intelligible information from an electronic health record, and wrote down the words you need to say in order translate from medical language to human language. We no longer had any complaints about how it was impossible to contact us.” |

As tragic as this was, it would’ve been the end of the story, had a representative from the Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor) not called Lyudmila’s spouse late one night with the news that Lyudmila had tested positive for coronavirus. The Rospotrebnadzor representative did not know any details of where, when, or why this test was administered. So began a different story.

Testing

Neither the doctors nor any other personnel informed Lyudmila’s relatives about the discovery of her infection. The one time during her hospital when the family managed to reach the resuscitation doctor on call, he stated that her “condition was stable, unchanged.” There was no mention of the coronavirus.

Lyudmila was tested for COVID while being admitted to the hospital, and that test came back negative, according to hospital workers who discussed the matter on condition of anonymity. After some time, she began to develop pneumonia in both of her lungs. When reached for comment by Proekt.media, the Moscow Health Department stated that Lyudmila manifested “signs of a respiratory illness” during her hospitalization, so they gave her another “several tests” and a radiological examination, which, again, reportedly turned up nothing. “She sat for a CT scan, which showed no changes in the lungs,” the department claims.

This is strange, according to a doctor who works with coronavirus-infected patients in one Moscow clinic (Translator’s note: this individual is referred to hereinafter as “the Moscow doctor”). Speaking to Proekt.media on condition of anonymity, he explained that a CT scan is almost guaranteed to pick up a coronavirus infection, because the latter has clear-cut radiological attributes (the so-called “ground glass opacity effect” in the lungs).

Only on May 30th, on the 13th day of Lyudmila’s hospitalization, did they give her a test that returned a positive result, according to Rospotrebnadzor.

At the same time, health officials do not acknowledge that Lyudmila contracted coronavirus in the hospital. In response to Proekt.media, the Moscow Health Department claims that, “no cases of hospital-acquired infections have emerged in the Yudin city clinical hospital.”

This is doubtful, considering that in the year prior to my relative’s death, she never left home, and she and her husband had self-isolated for the preceding three months. Coronavirus was not detected in her husband.

| Hospital Infections

Reducing the risk of hospital-acquired infections to zero is practically impossible, explains the deputy director of the National Medical Research Center for Phthisiology and Infectious Diseases, Vladimir Chulanov: “the risk can only be minimized by the following activities: controlling temperature, gathering epidemiological histories, and testing incoming patients. But considering that the incubation period is 14 days, a person who is already infected might not exhibit any symptoms.” Proper triage is another approach. Ideally, continues Chulanov, if a patient hasn’t been diagnosed yet, it’s desirable to place him or her in an isolation room. |

Quarantine

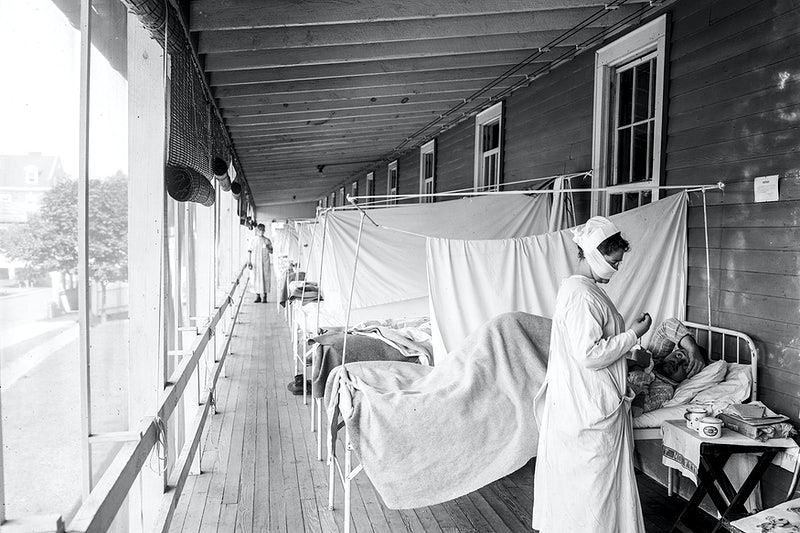

Even if Lyudmila was infected by the coronavirus on the day of the positive test, May 30th, she lied in open hospital wards for a minimum of five days. She alternated between five beds in the neurology ward and two beds in the intensive care unit. Early on the morning of June 3rd, several hours before her death, Lyudmila was located in the intensive therapy ward of the neurology department: photos taken by another patient at the request of Lyudmila’s family show her wearing an oxygen mask, without an assisted breathing apparatus.

Health Ministry documents stipulate that in cases where a patient show signs of COVID, medical staff are to “transfer the patient to an infection ward by calling for a specialized ambulance team.” The Moscow doctor who works with coronavirus patients confirms that, regardless of the severity of their case, all people confirmed to have coronavirus are required to be transported to a designated “COVID” building or to the clinic on Kolomenskiy Lane if there are no “COVID” beds in the hospital. Number Seven’s main facility, in his words, hardly meets the criteria for a “COVID” in-patient care center with its general ventilation, end-to-end hallways, and lack of airlocks.

The unit for coronavirus patients at Yudin hospital is located in a separate building on 1 Academic Millionshchikova street, nearly two kilometers away from the main facility. They did not send Lyudmila there.

If the hospital received the COVID-19 test only after Lyudmila’s death, then everyone who came into contact with her – patients and personnel – should take a polymerase chain reaction test. One nurse said that personnel regularly take the test, but she did not know about whether other patients are checked.

The Moscow doctor says that the epidemic primarily hit large clinics which were not refitted for the new virus, such as Number Seven’s main facility. The coronavirus penetrated all of these facilities equally, through personnel or patients, but it’s impossible to equip these facilities with airlocks, “red zones,” and turn off their ventilation, and so such hospitals became epicenters of viral spread among doctors and patients. “It was probably worthwhile to regard all pneumonia patients as coronavirus patients and to transport them to special hospitals, but as for how worthwhile this is and whether it’s feasible, nobody can currently tell,” says the doctor.

Statistics

It took an entire day to obtain and cremate the body – even at the end of the day, the queue at the Nikolo-Arkhangel’skiy crematorium consisted of 20 funeral processions. According to the funeral agent, the number of dead in the city has risen substantially over the past two months, and morgues cannot cope with the work. In particular, two funeral agents and one doctor stated that Hospital No. 15 in Vykhino had the busiest morgue in Moscow.

“In nine out of ten cases now, COVID is written on the second line of the death certificate, But never on the first line. My understanding is that it’s good for the hospital to show that a patient has COVID in order to receive money, but it’s not profitable to show increased mortality rates from COVID specifically.” So said one funeral agent, who showed several photographs of death certificates for deceased persons as evidence.

Media outlets has previously written about official death statistics in Russia, The Moscow Times being the first to do so. The same pattern is apparent in Lyudmila’s death certificate, which lists COVID as “an important condition that contributed to her death.”

* * *

Ever since the epidemic began, the Moscow doctor whom we spoke with on condition of anonymity only spends a few hours at home each night. He tells me, “Naturally, you’re looking at the history of COIVD through your own personal tragedy.” And he’s right.

One thought on “A Story of One Sickness (Translation)”